History of Gujarati Muslim Business Communities

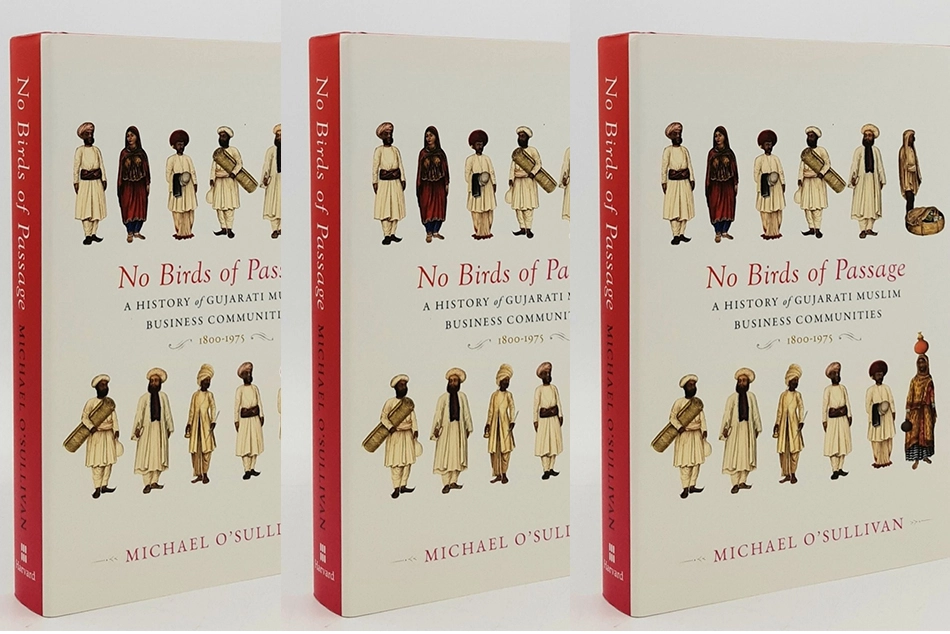

Michael O’Sullivan - a Senior Research Fellow at European University, Italy, has taken up their story in his book "No Birds of Passage: A History of Gujarati Muslim Merchant Communities (1800–1975)"

No Birds of Passage – A History of Gujarati Muslim Business Communities 1800-1975

Author: Michael O’Sullivan

Reviewer: Ghulam Arif Khan

Harvard University Press 2023

386 pp

eBook available

The Bohra, Khoja and Memon communities have long stood as a living emblem of the vibrant commercial spirit of Western India. These Gujarati Muslim groups, though small, rose to great heights of prosperity in the 19th century.

Constituting hardly 1% of South Asia’s Muslim population, they nevertheless punched far above their weight. With organizational flair, a sailor’s knack for the seas, and international ties that stretched across oceans, they carved out for themselves a position of remarkable strength and influence.

Through their tightly knit societies, they became movers and shakers of trade and industry, leaving behind an economic imprint that is visible to this day. Against all odds, these minorities within a minority managed to write a success story that few others could match.

Michael O’Sullivan - a Senior Research Fellow at European University, Italy, has taken up their story in his book "No Birds of Passage: A History of Gujarati Muslim Merchant Communities (1800–1975)".

In its pages, he paints a vivid picture of the Bohra, Khoja, and Memon way of life — their social fabric, their business ethics, and their resilience through the rough and tumble of history. He traces their voyage through political tempests, economic tides, and the twists and turns of changing times.

The book’s title itself carries weight.

Colonial historians once dismissed these communities as mere migratory birds, much like the East India Company’s agents or other European profiteers, driven solely by the lure of gain.

O’Sullivan sets the records straight: These were not birds of passage. Wherever they alighted, they took root and helped till the soil of local economies. Far from being fly-by-night traders, they became part and parcel of the regions they inhabited.

The study raises three key questions: What fuelled the meteoric rise of these communities in commerce?

How did their communal institutions — the Jamaat System, shape their progress?

And how did their wealth stir both admiration and envy, sometimes even sowing seeds of rivalry among Muslims and non-Muslims alike?

Before Bombay came into its own, Surat was the jewel of India’s commercial crown. And, even when Muslim maritime trade suffered a blow in the 18th century, Surat remained a hub in the wheel of regional and global commerce.

Gujarati Muslims, with one foot in Africa and the other in Asia, kept their trade networks alive.

Colonial policies may have clipped the wings of Indian industry in the 19th century, but these merchant groups managed to keep their flag flying.

Also Read: From bottom of social ladder to top – The story of Muslims in Britain

Take, for instance, the Memons’ migration from Sindh to Kathiawar — a shining example of their business acumen and adaptability.

By the close of the 18th century, they were not only weaving trade relations through their “Jamaat Khanas” - community centres but also negotiating deftly with local rulers. The saga of the Dhoraji Memons illustrates this well.

Tired of exorbitant taxes and the strangle hold of Hindu money lenders, they packed their bags, shifted to Junagadh, and eventually returned only, on invitation, when their bargaining power secured them favourable concessions.

Clearly, they knew when to bend with the wind and when to stand their ground.

Their horizons, however, stretched far beyond India’s shores. By the 18th century, Gujarati Muslim traders were charting routes from Jeddah to Zanzibar. Their skill at navigating these as not only linked them to global markets but also served as a shield against the roughness of recessionary Indian economy.

With the fall of the Mughals and the Marathas, Western India eventually passed into British hands. O’Sullivan notes how these communities and the Raj found common cause. In times of famine, natural calamity, war, and displacement, the British often extended them a helping hand.

Colonial courts too, treated them with greater leniency than other Indians, ensuring that their community systems remained intact. Merchants and their communities were bound together in a delicate relationship. The Jamaats functioned like corporate entities, pooling capital in the form of religious endowments.

Leaders held the purse strings and acted as arbiters in disputes, with expulsion as a deterrent. But where there is money, there is also mischief.

Internal rifts surfaced, especially over the scope of religious authority. The famous 1866 dispute, when leading Khoja merchants challenged Aga Khan I, ended with the British courts handing the Aga Khan sweeping powers over community property. Thus, began new intersections of Islamic law and colonial authority, reshaping the religious landscape of these groups.

Between 1880 and 1912, shifts in religious leadership further defined their identities. The Bohras and Khojas moved towards a model of central authority vested in a single religious head, while the Memons opted for a consultative style, relying on local ulema as guiding lights.

The lesson was clear: religious and social orders bend and sway with the winds of time.

The political climate after the First World War added new layers. These merchant communities were caught in a tug-of-war between the Khilafat Movement, Indian Nationalism, and imperial loyalty. While their allegiance to the British crown spared them persecution during the war, suspicions nevertheless lingered.

Some merchants and Jamaats dipped their toes into politics, even throwing financial weight behind nationalist causes — such as the Rangoon Memon Jamaat’s support for the Singapore rebellion.

The years 1923 to 1935 saw another storm brewing: The struggle for control over community endowments. What was once unquestioned authority came under fire, both from within and without. Could Waqf wealth serve the larger Muslim good, or must it remain locked within narrow boundaries? Such debates raged on.

The twilight years of the Raj brought further trials. Between 1933 and 1947, as British power waned, these communities found themselves caught between Islamic law and local traditions, striving daily to strike a balance. After the independence, the script changed once again. In Pakistan, they were targeted for economic failures post 1971. And, in India, whispers of doubt surrounded their loyalties. Both states, however, took pains to ensure their wealth did not slip into the other’s lap.

O’Sullivan’s real achievement lies in showing that these Jamaats were not mere institutional networks. They were human collectives, bound by kinship, trust, rivalries, and quarrels.

Their story is not just about ledgers and trade routes, but about the drama of these dynamic men and women struggling within the arena of faith, fortune, and modernity.

Against the backdrop of Islam’s encounter with capitalism, terms like “corporate Islam” and “Muslim capitalism” sound strikingly interesting.

Though the book is unmistakably an economic historian’s thesis, it is anything but dry. O’Sullivan draws on an array of sources — religious journals, travelogues, legal archives, biographical sketches, even old photographs — to breathe life into his account.

He does not forget the vital, often overlooked role of women either. His work opens windows for future scholarship. Covering history up to 1975, the book leaves one wondering about the last fifty years.

Today, the Bohras and Khojas seem still to be sailing with the wind of prosperity, their communal bonds largely intact.

The Memons, however, show signs of decline, both in wealth and cohesion.

Why this divergence?

The question begs urgent attention. Perhaps the other Muslim communities could take a leaf out of their book— learning how the power of collectivity can address the question of identity, and at the same time, become the engine of economic advancement.

[The writer, Ghulam Arif Khan, is a Commentator on socio-economic and political affairs, Editor, Public Speaker, Counsellor, Mentor & Entrepreneur. He is based in Mumbai.]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic