Mandal Vs Kamandal: The Political Theatre of November 7, 1990

November 7, 1990, is not merely a date in Indian parliamentary history; it is a glaring mirror held up to a nation grappling with its own contradictions.

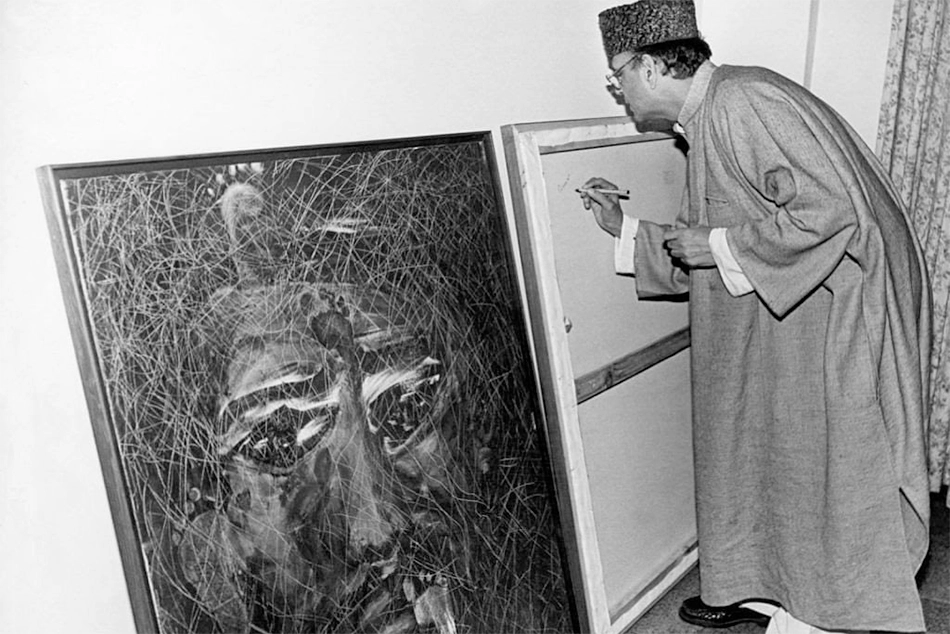

[VP Singh actually believed in social justice. The painting he is signing here is called “Downtrodden”... Siddharth's Echelon, Author, writes while sharing this image on X.]

Democracy on Trial

November 7, 1990, is not merely a date in Indian parliamentary history; it is a glaring mirror held up to a nation grappling with its own contradictions. On this day, the Lok Sabha convened not for routine legislations, not for economic planning, not even for mundane debates on bureaucratic minutiae—but to decide whether a Government committed to social justice should survive a political storm fueled by religious passions. The National Front Government, led by Prime Minister V.P. Singh, stood accused not of inefficiency or corruption, but of daring to implement one of the most progressive recommendations of independent India: The Mandal Commission report.

And yet, what should have been a routine parliamentary assertion of governance and constitutional supremacy transformed into an arena where religion, politics, and emotional populism collided violently. The country was forced to ask a question that should never have existed in a democracy: is one’s religious faith above the Constitution?

V.P. Singh, then the Prime Minister, did not mince words. His speech was a frontal assault on the emerging “Kamandalist” forces—a pejorative term now etched into political discourse—who sought to weaponize religion to undermine democratic governance. The acid-toned logic of Singh’s argument is often lost in contemporary recollections, but it deserves a scholarly re-examination today, especially as India braces for yet another Supreme Court verdict on the Ayodhya dispute.

Mandal vs. Kamandal – The Collision of Social Justice and Religious Nationalism

The political theatre of November 1990 was not merely a government facing a confidence vote; it was the collision of two ideological storms. On one side stood the Mandal Commission, a landmark initiative aimed at correcting centuries of systemic injustice against backward classes. On the other, the rising tide of Kamandalism—a crude fusion of religion and politics that sought to polarize the electorate by invoking emotive narratives rather than rational policy.

Singh’s four questions resonate even today:

- Is one’s religious faith above the Constitution or above the democratic setup?

- Should there be religious polarization in this country?

- Is the mixing of religion and politics desirable?

- Will the emotional integration of the country survive?

The irony is almost Shakespearean: a Prime Minister fighting for the Constitution, warning against theocratic tendencies, while his survival in office hung by a thread. It was a moment that revealed India’s fragility, not merely politically, but morally and socially. Singh understood that compromising on these points would not only betray the Constitution but also render the country a hostage to religious majoritarianism.

Faith above Law – The Spectre of Theocracy

Singh’s critique was scathing. The argument that religious faith could supersede law is the very definition of a theocratic State, and yet, the Kamandalist forces flirted with this dangerous notion openly. The Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi dispute was weaponized not as a legal question but as a litmus test for political survival. The Supreme Court’s directive to maintain status quo was treated as an irritant, a nuisance to be circumvented by emotional appeals rather than obeyed.

Singh’s words echo with prophetic weight: “If religion is placed above the Constitution, the State becomes theocracy in slow motion.” He foresaw the social polarization that would eventually grip northern India, including Punjab and Kashmir, and destabilize not just civilian life but the Armed Forces, the Police, and administrative cohesion. This was no abstract warning—it was an urgent call to preserve secular governance against the creeping menace of religious populism.

Politics of Polarization and the Price of Justice

Mandal was not a convenience—it was a moral imperative. It sought to enfranchise the backward classes, bring them into governance, and allow India’s social fabric to reflect the diversity it claims to celebrate. Yet, the Kamandalist backlash was relentless. Religious identity became the wedge to disrupt social justice, and political opportunism was cloaked in pious rhetoric.

Singh’s speech lays bare the absurdity: a government expected to survive on religious compliance rather than constitutional fidelity. He rejected the transactional morality of politics: “We are not bound to bow down to these systems just to complete our five years’ election term. We will prefer to keep ourselves away from power but continue to fight against injustice.”

This is a statement as revolutionary as it is bitterly satirical. Here was a Prime Minister willing to sacrifice political survival for justice, while the political class engaged in opportunistic theatrics, valuing votes over values.

Historical Roots of Religious-Political Polarization in India

To understand the drama of November 7, 1990, we must first appreciate the centuries-old undercurrents that made it inevitable. India has never been a tabula rasa; its society is layered with historical hierarchies, colonially codified divisions, and religious narratives weaponized for political purposes. The attempt by Kamandalist forces to cast religion as the arbiter of politics is not spontaneous—it is a meticulously rehearsed performance, centuries in the making.

The Colonial Legacy: Divide, Rule, and Conquer

Let us not indulge in nostalgia: British colonial administration was not just a governance experiment—it was a grand sociopolitical laboratory in which communities were measured, categorized, and pitted against each other. The census became the sword of divide-and-rule. Religious and caste identities were frozen into rigid categories that had previously been fluid.

The colonizers, in their administrative brilliance, realized early on that a fractured society is easier to govern. If Hindus and Muslims, upper castes and lower castes, could be convinced that they were existentially opposed, the political cost of unity would outweigh its benefits. And so, a seed was planted—a seed that would bloom into political polarization decades later.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, religion became a potent political instrument. Leaders who claimed to represent entire communities—often upper-caste elites—learned the art of mobilizing identity for power. This historical practice was inherited by post-independence India, and as V.P. Singh noted, the danger was never eradicated.

Partition Trauma and the Politics of Memory

Partition in 1947 was more than a geopolitical cataclysm—it was a trauma etched into the collective psyche of India and Pakistan alike. Millions were displaced, thousands slaughtered, and yet, the politics of memory refused to die. In northern India, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, narratives around Ram Janmabhoomi began to acquire new political significance, fusing religion and identity into electoral currency.

By the 1980s, these narratives were no longer marginal—they were weaponized. Religious polarization became an instrument to destabilize governments, mobilize crowds, and intimidate dissenting voices. V.P. Singh’s warning about the potential effects on Punjab and Kashmir was rooted in this painful history: communal polarization had already provoked insurgency in Punjab and fueled militancy in Kashmir. The risk of extending the same polarization into the heart of India was neither theoretical nor hyperbolic—it was historical inevitability waiting for opportunistic politics to ignite.

The Political Economy of Religion: A Strategic Weapon

The genius of Kamandalist strategy lies in its simplicity: emotional appeals, religious symbolism, and selective historical revisionism can outweigh facts, law, and logic. The Ram Janmabhoomi movement, framed as a moral and religious crusade, masked its true objective: political leverage.

Consider the audacity: V.P. Singh and his Government had taken steps to empower backward classes—a radical measure in a deeply stratified society. Yet, the backlash was orchestrated not through democratic debate but through religious mobilization. Temples and mosques became proxy battlefields for power. Faith, in this theater, was a tool to delegitimize governance and create instability.

Singh’s speech hits this point with surgical precision: if religion is above law, the country is no longer governed by reason, but by emotion—a dangerous, volatile, and morally corrosive equation.

The Fragile Architecture of Indian Democracy

India’s democracy is often celebrated as the largest in the world, but size alone is no guarantee of stability. The Constitution is robust, yet its foundations rest on social cohesion and respect for rule of law. The November 7 debate revealed that even constitutional architecture is vulnerable if social cohesion is deliberately undermined by those in pursuit of short-term power.

Singh was acutely aware that the stakes went beyond mere parliamentary arithmetic. The survival of democracy itself was in question if religion became the ultimate arbiter. The confidence motion was less about his Government and more about testing whether India could withstand the seduction of theocratic populism.

Lessons Unlearned: 1990 as Prologue

History is rarely kind to those who ignore it. The seeds of religious-political polarization sown during colonial rule, nurtured by post-independence elites, and weaponized in the 1980s exploded spectacularly in the 1990s. V.P. Singh’s Government became collateral damage, a casualty not of incompetence but of moral courage—a leader who refused to bow to communal opportunism.

And yet, the lesson remains largely unlearned. Contemporary politics continues to echo the same dynamics: identity is leveraged as currency, historical grievances are exaggerated, and the machinery of polarization thrives. In November 1990, India faced a test of constitutional integrity. Today, as Ayodhya returns to the headlines, the echoes of that test reverberate once more.

Mandal Commission Implementation – Backlash, Betrayal, and Social Revolt

The Mandal Commission was never meant to be an exercise in popularity; it was an act of justice long overdue. Tasked with identifying the socially and educationally backward classes and recommending measures for their upliftment, it held a mirror to a society steeped in centuries of systemic neglect. Its recommendations, particularly the extension of reservations in government jobs and educational institutions, were radical precisely because they challenged entrenched hierarchies.

And challenge they did. The backlash was immediate, ferocious, and entirely predictable—but no less tragic for being predictable. V.P. Singh’s government found itself at the eye of a political storm, as the privileged classes recoiled in horror at the prospect of sharing power, influence, and opportunity with those they had historically kept marginalized.

The Backlash: Upper Caste Angst on Full Display

The anger was loud, theatrical, and performative. Students staged massive protests across northern India; streets became battlefields for slogans that betrayed entitlement more than ideology. The logic, such as it was, amounted to: “Why should they rise when we have spent centuries climbing to the top?” This wasn’t a protest against policy; it was a protest against justice.

V.P. Singh saw it clearly. He understood that resistance to Mandal was not about numbers, not about governance, not about administrative feasibility—it was about power, caste privilege, and the refusal of a dominant class to tolerate equality. He framed the debate in moral terms: either the Government survives, or the country survives in its secular and democratic essence. The choice, as he put it, was non-negotiable.

Kamandalist Opportunism: Religion as a Wedge

The political genius—and cruelty—of Kamandalist forces lay in their ability to link the Mandal recommendations to religious polarization. The “othering” of backward classes was seamlessly fused with religious rhetoric: if the oppressed rise, the sanctity of the Hindu social order is threatened. Temples became stages for political agitation; religion was no longer spiritual guidance—it became a cudgel to beat down social reform.

Singh’s words ring sharper in retrospect: “We have to see whether religion and politics can be mixed up and whether there would be religious polarization in this country.” The Mandal backlash, when combined with the simmering Ram Janmabhoomi agitation, created a perfect storm. Politics had mutated into an identity game where religion and caste were the only currencies, and constitutional morality was a distant memory.

Betrayal from Within: Allies Turned Foes

No political battle is complete without betrayal. The National Front, a coalition fragile by design, witnessed first-hand how political expediency trumps ideology. Allies who had once championed social justice began to whisper, cajole, and ultimately turn against the very measures they had once supported.

Singh’s speech exposes this duplicity with candid bitterness. He recounts his tenure in the Finance Ministry and Defence Ministry, where clashes with established systems led to his removal. Now, as Prime Minister, even his attempt at implementing social justice made him a target. The moral of the story is brutal yet simple: in India, moral courage is often the fastest route to political isolation.

Social Revolt and Political Awakening

Yet, not all consequences of Mandal were negative. The implementation catalyzed a political awakening among backward classes. For the first time, those historically excluded from power realized that their voices mattered. Mere discussion was insufficient; representation was necessary. Mandal was more than policy—it was an invitation to participate in governance, to claim a stake in India’s destiny.

Singh captured this truth succinctly: “Unless weaker sections participate in the power structure, whether it is in this House or in the bureaucracy, their problems cannot be solved.” The courage of implementing Mandal was not to curry favor; it was to create structural change. It was a fight for justice, and justice, as history repeatedly demonstrates, is rarely gentle or popular.

Irony and Tragedy: Democracy Held Hostage

The irony of November 1990 lies in the tragic theatre of democracy itself. A government committed to social justice was brought to the brink of collapse, not because it had failed in governance, but because it dared to threaten entrenched social hierarchies. The theater of the streets, the frenzy of identity politics, and the shadow of religious polarization combined to make governance almost impossible.

Singh’s steadfast moral clarity contrasts sharply with the opportunism around him. While allies schemed, agitators shouted, and crowds demanded theatrical concessions, the Prime Minister remained anchored to principles. His was not a politics of convenience but a politics of courage—a politics that prioritized the Constitution, justice, and the dignity of marginalized communities over survival in office.

The Lessons of Mandal: Courage vs. Convenience

The Mandal implementation episode teaches a bitter truth: in a society accustomed to hierarchy, reform is revolutionary. Justice is confrontational. Political survival often depends on surrendering principle, and history is usually written by those who choose convenience over courage.

Yet, the Mandal experiment also demonstrates that structural reform is possible. The fight for backward classes did not end with political setbacks—it set the stage for future struggles, inspiring generations to claim space in governance, education, and society at large. V.P. Singh’s defiance exemplifies the painful but necessary intersection of ethics and politics: leadership often requires embracing temporary unpopularity for long-term justice.

The Judiciary and Constitutional Morality – Guardians or Spectators?

In November 1990, India’s judiciary stood at a crossroads, a silent observer to the theatrical chaos unfolding in the Lok Sabha and the streets. V.P. Singh’s speech on that fateful day underscored a truth that is as relevant today as it was then: the Constitution is only as strong as those willing to defend it. Courts, like any institution, can issue orders, interpret laws, and assert authority—but when religion masquerades as politics, even judicial decrees can be ignored, twisted, or ridiculed.

The Supreme Court and the Status Quo

The Allahabad High Court had issued a directive to maintain the status quo at the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi site, clearly stating that neither demolition nor interference with worship should occur until a final verdict. Simple. Clear. Constitutional. Law.

And yet, simple and clear often have little power against the storm of mass hysteria, political opportunism, and religious theater. Singh’s observation—“If one’s religious faith is above the Constitution and the court, it is possible only in a theocratic State”—was not rhetorical flourish; it was a factual diagnosis of what happens when emotion substitutes for law, when faith is elevated above reason.

The courts were the guardians of justice, but the Kamandalist forces sought to reduce them to spectators, to make their authority impotent in the face of emotional mob politics. The tragedy of 1990, as Singh predicted, was not merely political—it was constitutional.

Constitutional Morality vs. Political Expediency

India’s Constitution is not a set of suggestions—it is a radical, revolutionary document that attempts to balance justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity in a society steeped in hierarchical inequities. Yet, in 1990, constitutional morality was under assault. Political leaders and activists openly suggested that religious sentiment should override law, effectively proposing a parallel moral universe governed by faith rather than reason.

Singh’s foresight was brutal: democracy cannot survive if governance is hostage to emotion and identity politics. By standing firm on Mandal and defending the judicial status quo at Ayodhya, he forced the nation to confront a discomfiting question: would India continue as a secular democracy or drift toward theocracy, clothed in the language of piety?

In parliamentary terms, the confidence vote was less about arithmetic and more about principle. Singh’s moral clarity highlighted a recurring paradox: politics rewards opportunism and punishes principle. The Constitution, meanwhile, remained a fragile relic, enforceable only when citizens and leaders are willing to defend it.

The Judiciary as a Moral Compass

Courts are designed to enforce justice, not to comfort the powerful. Yet, when law clashes with religious populism, the judiciary’s authority is tested in the harshest way. Singh warned that ignoring constitutional mandates in favor of religious polarization could destabilize Punjab, Kashmir, and the entire social fabric. History, as he implicitly reminded the House, had already demonstrated the consequences of such neglect: insurgency, sectarian violence, and political fragmentation.

The judiciary, therefore, was both guardian and warning. Its orders on the Ayodhya site were clear, but enforcement depended on political will—a will that was conspicuously absent in the frenzy of November 1990. Singh’s speech, when read with judicial pronouncements, reads almost like a blueprint for crisis management, one that was ignored at peril to the nation.

The Moral Hazard of Religious Populism

Singh’s indictment of mixing religion and politics is, in hindsight, prophetic. Religious populism creates moral hazard: it rewards leaders who exploit faith for power and punishes those who adhere to justice. In 1990, the Prime Minister faced this directly. By insisting that faith cannot supersede law, he positioned himself as both target and teacher—a moral lesson embodied in human flesh.

The acid truth is stark: if a government cannot enforce constitutional morality without being destabilized, what hope does society have? Courts can write orders, but if political and social actors choose defiance, law becomes symbolic, and governance becomes performative theater. This is precisely the dynamic Singh sought to expose.

Lessons for Contemporary India

The judiciary’s role in 1990 offers a mirror to the present. As the Ayodhya verdict again grabs headlines, Singh’s warning resonates: the health of democracy is measured not by the rhetoric of politicians but by adherence to law, equality, and constitutional morality.

Religious sentiment, when converted into political weaponry, has the capacity to undermine not just governments but the very principles on which India is built. Singh understood that survival in office is meaningless if the Constitution is undermined. The judiciary, in this context, is the last line of defense—but even it is powerless without public and political support.

Acid Reality Check

Let us not romanticize the judiciary. The courts are neither omnipotent nor infallible; they can only act within the constraints of political reality. Singh’s speech lays bare this tension: law exists, morality exists, but power is fickle, and mobs are louder. Democracy is fragile not because laws fail but because humans—leaders, citizens, and institutions—fail to respect them consistently.

November 7, 1990, is a reminder that constitutional morality is not self-enforcing. It requires courage, persistence, and a willingness to withstand temporary unpopularity. Singh had that courage; the political establishment largely did not.

V.P. Singh’s Legacy and Modern Parallels – Prophecy and Politics

History has a cruel sense of irony: the courage that destabilized a government in 1990 is now widely celebrated in retrospect, yet the patterns Singh warned about continue to plague Indian democracy. His stand was not merely political—it was moral, constitutional, and, in many ways, prophetic. In examining his legacy, one cannot help but note the eerie parallels between November 1990 and today’s political climate.

Courage in Office: A Moral Compass Amid Opportunism

V.P. Singh’s leadership style was a radical anomaly. He prioritized justice over survival, principle over power, and constitutional morality over expediency. His famous line resonates decades later:

“We are not bound to bow down to these systems just to complete our five years’ election term. We will prefer to keep ourselves away from power but continue to fight against injustice.”

This was no empty rhetoric. Singh faced orchestrated opposition, betrayal from allies, and the full weight of religiously mobilized political anger. And yet, he remained unwavering.

Modern politics, by contrast, rewards compromise, expediency, and, often, moral cowardice. Leaders today are judged by their ability to survive elections, not by their adherence to constitutional principles. Singh’s legacy is a stark reminder that ethical leadership is both rare and costly—a price many are unwilling to pay.

Prophetic Warnings about Polarization

Singh’s insight into the dangers of mixing religion and politics was unsettlingly accurate. He warned that religious polarization could destabilize not just governance but the entire social fabric, including Punjab, Kashmir, and other sensitive regions.

Fast-forward to the 21st century: the same playbook is being used—identity politics, religious rhetoric, and emotional populism to achieve short-term electoral gains. The political theatre that toppled Singh’s government has not disappeared; it has evolved, becoming more sophisticated, media-driven, and nationally pervasive.

His speech is a cautionary tale: democracy is fragile when law and reason yield to emotional mobilization. Those who ignore this lesson do so at their peril, for history has a habit of repeating itself with increased intensity.

Mandal, Social Justice, and the Modern Struggle

The Mandal Commission implementation, once a cause of uproar, has transformed into a benchmark for social justice. Yet, the struggle for backward class representation remains unfinished. Singh’s insistence on involving marginalized communities in governance remains relevant today. Without representation, laws and policies are mere paper exercises.

The modern Indian political landscape—where social justice, caste, and religion intersect—demonstrates the enduring relevance of Singh’s fight. Leaders who fail to internalize this lesson risk repeating the mistakes of the past: prioritizing votes over justice, convenience over courage, and opportunism over principle.

The Enduring Threat of Kamandalist Politics

The term “Kamandalist” may seem dated, yet the forces it described remain active, adaptive, and potent. Religion continues to be a weaponized instrument in electoral politics. Narratives around sites like Ayodhya, communal tensions, and identity politics persistently resurface, often to distract from governance failures or social inequities.

Singh foresaw the danger: when religion becomes a tool for power, democracy suffers. When law is subordinated to faith, institutions weaken. When social justice challenges entrenched hierarchies, reactionary forces mobilize to destabilize the state. This triad of threats—faith, polarization, and privilege—is as alive today as it was in 1990.

Moral Leadership as a Benchmark

Singh’s legacy is not just historical—it is prescriptive. Modern leaders are often tested not by policy complexity but by their willingness to uphold justice in the face of adversity. Singh’s refusal to compromise principle for political survival sets a benchmark that contemporary politics rarely meets.

In an era of media frenzy, instant gratification, and political cynicism, his words resonate with almost prophetic urgency:

“Our fight for the causes dear to us will continue. We will continue to fight for those who have been exploited, suppressed, and neglected.”

Leadership, Singh demonstrated, is not about power retention; it is about ethical courage, the defense of constitutional morality, and the relentless pursuit of justice.

Irony, Satire, and Contemporary Parallels

It is bitterly ironic that a Prime Minister ousted for defending justice is now remembered as a visionary, while those who exploited emotion and polarization often enjoy political longevity. Singh’s experience is a darkly humorous mirror to modern India: opportunism rewards itself, moral courage is punished, and lessons from history remain unlearned.

Yet, the satire is not complete without reflection: the very forces that destabilized Singh’s government in 1990 are still active, often thriving in more sophisticated guises. The stage, it seems, is set for history to replay itself—unless citizens, courts, and ethical leaders intervene decisively.

Kamandalist Forces – Then and Now

If November 7, 1990, was a test of India’s constitutional resilience, Kamandalist forces were its insurgent antagonists—religion turned weapon, tradition turned tool, and faith turned theatre. To call them merely political actors would be charitable; they were—and continue to be—a hybrid of religious zeal, caste entitlement, and opportunistic ambition, a force as durable as it is corrosive.

Kamandalism Defined

The term “Kamandalist” derives from the symbolic weapon of Hindu ascetics—the kamandal—but here, the symbolism is inverted: what should have represented spiritual asceticism and moral discipline was repurposed into a cudgel for political advantage. Kamandalist politics is a precise formula: identify a religious narrative, exaggerate historical grievances, amplify fear, and mobilize masses through emotive rhetoric.

In 1990, this formula was deployed brilliantly: the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation was fused with caste anxieties triggered by Mandal, creating a cocktail of polarization potent enough to destabilize a government committed to social justice. Singh recognized it as such. He understood that Kamandalist politics does not engage in debate—it performs, agitates, and intimidates.

The Strategic Exploitation of Religion

Religion in India, when weaponized, is never neutral. It becomes a mobilization engine, an identity marker, and a shield against accountability. Kamandalist forces leveraged this to maximum effect. Temples and religious events were not sacred spaces; they were stages for political theater, where morality was manipulated and history was rewritten for immediate gains.

The genius—and audacity—of Kamandalist politics lies in its simplicity: it never wins by persuasion, only by emotional dominance. The Supreme Court’s rulings, parliamentary debates, and policy measures become irrelevant when faith is redefined as moral law, untouchable and unquestionable. Singh’s warning was prescient: when religion is weaponized for politics, governance is hostage, and democracy becomes performative rather than functional.

The Persistent Caste-Religion Nexus

Kamandalist forces understood the intersectionality of caste and religion long before social scientists codified it. By linking Mandal’s backward class empowerment with religious alarmism, they created a dual threat: any attempt at social justice could be framed as a threat to the “cultural” or “religious” order.

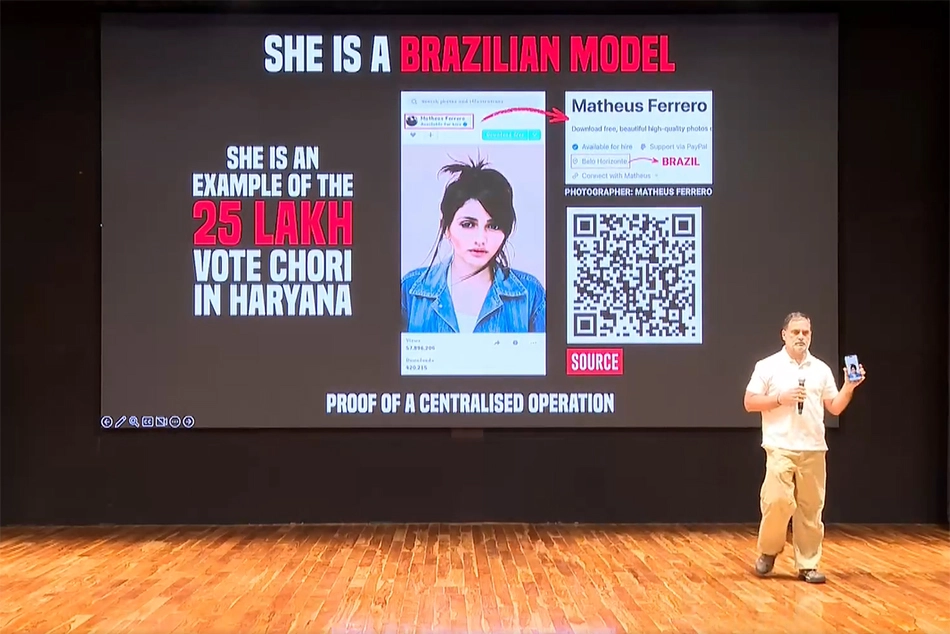

This nexus remains active today. Policies aimed at redistributive justice, minority protections, or secular enforcement are constantly reframed as attacks on majority identity, often accompanied by media spectacles, orchestrated protests, and street theatrics. The playbook hasn’t changed—only its execution has evolved, incorporating television, social media, and electoral micro-targeting.

Political Opportunism and Moral Bankruptcy

The brilliance of Kamandalist forces lies in opportunism, the audacity to weaponize morality while embracing expediency. Political actors exploit fear, manipulate history, and misrepresent religion, all while presenting themselves as moral arbiters. Singh’s speech exposes this starkly: a government committed to social justice and constitutional fidelity is demonized, while those fomenting unrest are celebrated as defenders of faith.

The irony is bitter: morality becomes performative, principle is punished, and opportunism is rewarded. Kamandalist politics, in essence, thrives on societal cognitive dissonance—people are asked to believe that injustice is justice, that fear is courage, and that privilege is entitlement.

Modern-Day Kamandalism

The techniques pioneered in 1990 persist, now amplified by technology and media. Social media platforms magnify fear, selective history fuels outrage, and political messaging transforms religion into both shield and sword. Narratives around Ayodhya, temple politics, and caste entitlement are reused, repackaged, and redeployed with uncanny consistency.

The tragedy is that the consequences are identical: polarization, weakened governance, undermined constitutional authority, and distracted citizens. Democracy, Singh warned, cannot survive in such an environment without courageous leadership and vigilant institutions. Yet, history shows us that courage is often scarce, and institutions are often reactive rather than proactive.

Acid Reality Check: Democracy Under Siege

Kamandalist politics is not a relic; it is a systemic feature of India’s political ecosystem. The moral satire is sharp: those who exploit faith are lauded, those who defend law are vilified, and society oscillates between frenzy and apathy. Singh’s warnings were not dramatic flourishes—they were diagnoses of a structural threat that has only grown more sophisticated with time.

The ultimate irony: Kamandalist forces rely on division, but democracy, at its core, demands cohesion. By amplifying religious and caste differences for political gain, they weaken both the polity and the state. Singh’s speech on November 7, 1990, becomes more than a historical artifact—it is a manual in moral clarity, a critique of opportunism, and a call to arms for constitutional fidelity.

Lessons for Contemporary India – Ayodhya, Judiciary, and Social Justice

History is rarely kind to those who ignore it, and India’s modern political landscape repeatedly demonstrates this uncomfortable truth. The events of November 7, 1990, the Mandal implementation, and V.P. Singh’s principled stand offer a grim template for contemporary India. If ignored, these lessons ensure repetition of past mistakes, yet they are ignored all too often, to the detriment of democracy, secularism, and social justice.

The Perils of Religious Polarization

Singh’s warning was stark: mixing religion with politics threatens the social, emotional, and administrative fabric of the country. This is not hyperbole—it is historical reality. Punjab had already seen insurgency, Kashmir was simmering, and northern India was on the edge of communal tension. Today, these warnings echo in the context of the Ayodhya verdict, media spectacles, and the politics of identity.

The lesson is clear: religious polarization is not merely a political tool; it is a national hazard. It weakens institutions, fuels mistrust, and divides citizens against each other. Leaders, institutions, and citizens alike must recognize the long-term cost of allowing faith to be weaponized for short-term political gain.

Constitutional Morality Must Be Non-Negotiable

The courts, the Constitution, and legal mandates are not suggestions—they are the scaffolding of democracy. Singh emphasized that faith cannot supersede law. Yet, history shows that when constitutional morality is treated as optional, governance becomes performative, law becomes symbolic, and democracy becomes fragile.

The lesson is harsh but necessary: democracy requires active defense of constitutional principles, even when inconvenient. Leaders must prioritize justice over votes, institutions must enforce the law impartially, and citizens must hold power accountable. Anything less invites the slow creep of theocracy and the erosion of civil liberties.

Social Justice Cannot Be Deferred

Mandal was more than policy—it was moral rectification. Backward classes, historically marginalized and excluded from governance, were finally being granted a stake in India’s future. Singh’s insistence on inclusion as a prerequisite for justice is as relevant today as it was then.

The lesson is unambiguous: social justice cannot be postponed for political expediency. Without representation in administration, governance is performative, laws are ineffective, and societal inequities persist. Any attempt to undermine or delay social justice for political convenience is a betrayal of both the Constitution and the ethical obligation to the nation.

Vigilance Against Opportunism

The Kamandalist forces exemplify the dangers of moral and political opportunism. Religion, caste, and identity are weaponized to destabilize governance, manipulate narratives, and consolidate power. Singh’s 1990 speech exposed this strategy in unflinching detail, yet contemporary politics continues to replicate it with technological sophistication: social media amplification, misinformation campaigns, and orchestrated public sentiment now operate alongside traditional religious mobilization.

The lesson is clear: democracy demands vigilance. Citizens must recognize manipulation, question emotive appeals, and demand accountability. Leaders must resist the temptation to exploit faith for short-term gain. Institutions must remain independent and assertive. Ignorance or apathy invites repetition of past mistakes.

Leadership is Courage, Not Convenience

Singh’s moral courage offers a template for leadership: prioritize justice over personal or political survival. This is a lesson that transcends time. Political leaders today face similar dilemmas—balancing constitutional obligation with populist pressures, enforcing law while managing public sentiment, and implementing reforms despite entrenched resistance.

The lesson resonates: ethical courage is rare but indispensable. Without it, democracies do not merely stagnate—they regress, rewarding opportunism and punishing principle. Singh’s November 7 stand remains a beacon, reminding contemporary India that compromise in the name of expediency is a slippery slope toward moral decay.

Democracy Requires Active Citizenship

Finally, Singh’s warnings underscore the necessity of an engaged, vigilant citizenry. Democracy is not preserved by laws alone; it requires participation, awareness, and moral courage from citizens. Passive acceptance allows polarization, opportunism, and injustice to thrive.

The lesson is uncompromising: citizens must defend secularism, uphold constitutional morality, and demand that justice—not emotion, not identity, not fear—dictates governance. November 7, 1990, is a cautionary tale, a mirror reflecting the fragility of India’s democratic experiment when courage, justice, and participation falter.

Conclusion – Justice, Democracy, and the Future of Secular India

November 7, 1990, was more than a parliamentary session—it was a moral crucible. V.P. Singh, facing a confidence vote, dared to prioritize principle over political survival, justice over expediency, and constitutional morality over opportunism. What he demonstrated that day was neither theatrical nor sentimental; it was a blueprint for ethical leadership, a mirror reflecting both the promise and peril of India’s democratic experiment.

Today, decades later, the echoes of that day are unmistakable. The Ayodhya verdict, continuing caste-based polarization, and the resurgence of religion as a political instrument remind us that the lessons Singh delivered are neither obsolete nor academic. They are urgent, immediate, and non-negotiable.

The Fragility of Democracy

Singh’s warnings were prescient: democracy is fragile when faith replaces law, when emotion replaces reason, and when opportunism replaces principle. Kamandalist forces, then and now, thrive on this fragility. They weaponize identity, rewrite history, and manipulate fear to destabilize governance and erode constitutional morality.

The acid truth is brutal: India’s democracy is only as strong as its commitment to justice. When political convenience trumps principle, law becomes symbolic, institutions weaken, and the nation drifts toward polarization and chaos. November 1990 was a rehearsal; the contemporary political landscape reveals the sequel—more sophisticated, more pervasive, but fundamentally the same threat.

Justice as the Non-Negotiable Imperative

Mandal was not merely a policy—it was a moral reckoning. V.P. Singh’s insistence on empowering backward classes, ensuring representation, and implementing social justice was a direct challenge to centuries of entrenched hierarchy. The lesson is eternal: justice cannot be deferred for electoral expediency. Representation cannot be sacrificed for popularity. Moral courage cannot be substituted with political convenience.

Singh’s speech resonates with prophetic clarity: “Our fight for the causes dear to us will continue. We will continue to fight for those who have been exploited, suppressed, and neglected.” Justice is not optional; it is the bedrock upon which democracy stands. Ignore it at your peril.

The Perennial Threat of Kamandalist Politics

Kamandalist forces are not relics; they are adaptive, resilient, and relentless. Religion, caste, and identity are repeatedly repurposed as instruments of political mobilization. History, as Singh demonstrated, has a brutal consistency: those who exploit faith are rewarded, those who uphold law and justice are punished.

The satirical, acid-toned reality is inescapable: India often celebrates those who disrupt democracy in the name of morality while vilifying those who defend it. The theatre of politics masquerades as governance, and the moral compass is frequently ignored until the damage becomes irreversible. Singh’s November 7 speech is a stark reminder that this cycle is neither accidental nor harmless—it is deliberate, structural, and dangerous.

Vigilance, Leadership, and Citizen Responsibility

If the past teaches anything, it is that ethical leadership is rare, but necessary, and vigilant citizenry is indispensable. Democracy is not preserved by courts alone, by laws alone, or by constitutions alone. It requires citizens who recognize manipulation, demand accountability, and insist that justice—not fear, emotion, or identity—dictates governance.

V.P. Singh exemplified this courage. He refused to compromise principle for survival, law for popularity, and justice for convenience. Modern leaders, in his shadow, are tested by the same dilemmas. The lesson is unyielding: leadership without courage, institutions without enforcement, and citizens without engagement are a recipe for democratic decay.

Prophetic Satire: The Mirror We Refuse to See

History is cruelly satirical. The very forces that destabilized Singh’s government are still active, now more sophisticated, technologically enhanced, and nationally pervasive. Yet the pattern remains identical: moral courage punished, opportunism rewarded, constitutional morality ignored.

Singh’s speech, in retrospect, reads as both prophecy and indictment. It is a moral compass, an acid critique of political expediency, and a call to action. Ignore it, and the nation repeats the same mistakes; internalize it, and democracy has a chance to survive in principle as well as in form.

The Unfinished Battle for Secularism

The struggle that defined November 7, 1990, is unfinished. Secularism, justice, and constitutional morality are not guaranteed—they are fought for, defended, and demanded, every day. Singh’s courage reminds us that governance is not about survival; it is about responsibility. Democracy is not about expediency; it is about principle. Justice is not about legislation alone; it is about inclusion, representation, and empowerment.

As India confronts Ayodhya, caste tensions, and the continuing fusion of religion and politics, the lessons of November 1990 remain painfully urgent: defend the Constitution, resist opportunism, empower the marginalized, and never allow faith to supersede law.

Final Acid Truth

The acid, bitter, and unavoidable truth is this: nations fall not because of external enemies, but because of internal moral weakness. India’s internal test in 1990 was a warning shot; the replay is underway, more sophisticated but no less dangerous. Singh’s words remain a clarion call: choose justice over convenience, principle over survival, law over faith, courage over fear. The alternative is unthinkable—the slow decay of democracy, the triumph of opportunism, and the betrayal of every promise the Constitution made to its citizens.

November 7, 1990, is not history—it is a lesson, a warning, and a mirror. V.P. Singh faced it with courage. India must do the same.

[The writer, Dr. Tata Sivaiah: A mathematician who counts revolutions, not riches. He decodes India’s buried conscience with surgical satire and historical fire – from Buddha’s enlightenment to Ashoka’s remorse. Part rebel, part researcher, he turns every article into an uprising and every paragraph into a protest. He doesn’t rewrite history – he exposes the lies that rewrote it.]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic