Modi Model of Governance: A Greater Threat Than The Emergency?

The Modi era, is more dangerous because it represents a slow, systematic, and potentially permanent undermining of the Constitution and its basic structure

The Emergency period under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi is widely regarded as one of the darkest chapters in India’s democratic history. For 21 months, civil liberties were suspended, the press was censored, and political opponents were jailed. In recent years, even Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has publicly acknowledged that the Emergency was a “mistake,” stating, “What happened during the Emergency was wrong. That was a mistake. And my grandmother said as much.”.

Yet, a growing number of scholars, journalists, and political analysts argue that the current era under Prime Minister Narendra Modi poses an even greater threat to the Indian Constitution and its basic structure. Unlike the Emergency, which was a declared and time-bound suspension of democracy, the Modi era is marked by a slow, systematic, and potentially permanent undermining of constitutional values and institutions.

The Emergency Period

The Emergency was a period of overt authoritarianism. The government suspended fundamental rights, censored the press, and jailed thousands of political opponents. The Constitution was amended to grant the executive sweeping powers, and the judiciary was pressured to conform to the government’s line. However, the Emergency was declared openly, and its excesses were visible to all. When the Emergency ended, the democratic process was restored, and most of the changes made during that period were rolled back. The Indian electorate decisively voted out the Congress government in 1977, demonstrating the resilience of Indian democracy.

Even at its worst, the Emergency did not fundamentally alter the basic structure of the Constitution. The judiciary, despite being under pressure, asserted itself with the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case, which established the “basic structure doctrine.” This doctrine has since acted as a bulwark against constitutional amendments that threaten democracy. The Emergency was a dark chapter, but it was a declared and temporary suspension of democracy, not a permanent transformation of the Indian state.

The Modi Era: A Decade of Transience and Erosion

In contrast, the Modi era is marked by a slow, systematic, and potentially permanent undermining of constitutional values and institutions. The changes are not always visible or dramatic, but they are profound and far-reaching. The Modi government has used its electoral mandate to centralize power, undermine institutions, suppress dissent, and reshape the Indian republic in ways that may be difficult to reverse.

One of the most significant differences between the Emergency and the Modi era is the nature of the threat to democracy. The Emergency was a declared aberration, a temporary suspension of normalcy. The Modi era, on the other hand, represents a slow erosion of democratic norms, often under the guise of legality and national interest. This makes it harder to mobilize public opinion and resist the changes. The use of technology, the co-option of institutions, and the targeting of dissenters have created an environment where fear and conformity are the norm. The government’s narrative of nationalism and development is used to justify actions that would have been unthinkable in earlier times. The result is a society where the space for dissent, debate, and diversity is shrinking.

Undermining Constitutional Institutions

One of the hallmarks of the Modi era has been the systematic undermining of constitutional institutions. The Supreme Court, Election Commission, Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and Enforcement Directorate (ED) have all faced allegations of executive interference. The independence of these bodies, which are meant to act as checks and balances, is being eroded, raising concerns about the future of Indian democracy. The Supreme Court, once seen as the guardian of the Constitution, has been criticized for its reluctance to take up key constitutional cases and for its perceived deference to the executive. The Election Commission, which is supposed to ensure free and fair elections, has faced allegations of bias and inaction in the face of electoral violations by the ruling party.

The CBI and ED, which are meant to investigate corruption and financial crimes, have been accused of being used as tools to target political opponents and silence dissent. The frequent use of these agencies against opposition leaders, activists, and journalists has created an atmosphere of fear and intimidation. The independence of these institutions is crucial for the functioning of a healthy democracy, and their erosion is a cause for grave concern.

The Misuse of Governors: From Rubber Stamps to Hammers

Another disturbing trend in the Modi era has been the misuse of governors. The office of the governor was intended to be a neutral constitutional authority, acting as a bridge between the Centre and the states. However, in recent years, governors have increasingly acted as agents of the central government, often undermining democratically elected state governments. The use of governors to destabilize opposition-ruled states, delay the formation of governments, and interfere in legislative processes has become commonplace.

In several instances, governors have refused to invite the largest party or coalition to form the government, instead facilitating the formation of governments by the BJP or its allies. In Maharashtra, for example, the governor’s actions during the government formation crisis in 2019 were widely criticized as partisan. In West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, governors have clashed with state governments, often acting as obstacles rather than facilitators. The role of the governor has shifted from being a “rubber stamp” to becoming a “hammer” used to undermine the federal structure of the Constitution.

This trend is particularly dangerous because it strikes at the heart of India’s federal system. The Constitution envisages a balance of power between the Centre and the states, with the governor acting as a neutral arbiter. The politicization of the governor’s office undermines this balance and threatens the autonomy of state governments. It also sets a dangerous precedent for the future, where the central government can use the governor’s office to subvert the will of the people in the states.

Subversion of Federalism

The misuse of governors is part of a broader pattern of centralization of power in the Modi era. The central government has increasingly encroached on the powers of the states, often using legislation, executive orders, and financial controls to assert its authority. The abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, the imposition of President’s Rule in opposition-ruled states, and the centralization of fiscal powers through the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime are all examples of this trend.

The GST, while economically significant, has been criticized for reducing the fiscal autonomy of the states. The central government’s control over GST revenues has made states more dependent on the Centre for funds, undermining their ability to pursue independent policies. The use of centrally sponsored schemes, often with the Prime Minister’s name attached, has further eroded the autonomy of the states. The result is a weakening of the federal structure of the Constitution, with the Centre increasingly dictating terms to the states.

Undermining Secularism

Secularism is a cornerstone of the Indian Constitution, and its erosion is one of the most worrying trends of the Modi era. During the Emergency, secularism was not directly attacked, even though civil liberties were suspended. In contrast, the Modi era has witnessed a rise in majoritarian policies and open communal rhetoric. The passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC), and the increasing frequency of communal violence have raised fears about the erosion of India’s secular fabric.

Critics argue that these policies are designed to marginalize religious minorities, particularly Muslims, Christians, and redefine Indian citizenship along religious lines. The CAA, which provides a path to citizenship for non-Muslim refugees from neighboring countries, has been widely criticized as discriminatory. The NRC, which requires citizens to prove their citizenship through documentation, has created fear and uncertainty among millions of people, particularly in Assam. The combination of these policies has led to widespread protests and violence, with the government responding with force and repression.

The rise in hate crimes, lynchings, and discriminatory laws against minorities has created an atmosphere of fear and insecurity. Human rights organizations have documented a sharp rise in violence against Muslims and Dalits, often with impunity. The targeting of NGOs working with minority communities, the use of anti-conversion laws, and the demonization of dissenters as “anti-national” have further contributed to the erosion of secularism.

Freedom of Press and Expression

Freedom of the press is a fundamental pillar of democracy, and its suppression is a hallmark of authoritarian regimes. During the Emergency, press censorship was overt and official. Newspapers were shut down, and editors were jailed. In the Modi era, the suppression of the press is more covert but equally effective. Media houses critical of the government face income tax raids, withdrawal of government advertising, and threats of legal action. Journalists have been arrested under draconian laws, and self-censorship is rampant. India’s ranking in the World Press Freedom Index has steadily declined, reflecting the growing challenges faced by independent media.

The government has also used technology to control the flow of information. Internet shutdowns, particularly in Jammu and Kashmir, have been used to suppress dissent and prevent the spread of information. Social media platforms have faced pressure to remove content critical of the government, and new regulations have been introduced to increase government control over digital media. The combination of legal, economic, and technological pressures has created an environment where independent journalism is increasingly difficult.

Judicial Independence Under Threat

The judiciary was under pressure during the Emergency, but it also laid down the basic structure doctrine, which has since acted as a bulwark against constitutional amendments that threaten democracy. In the Modi era, there are increasing allegations of executive interference in judicial appointments and functioning. The delay in appointments, the transfer of inconvenient judges, and the lack of action on key constitutional cases have raised questions about the judiciary’s independence.

The Supreme Court’s reluctance to take up cases related to the abrogation of Article 370, the CAA, and electoral bonds has also been widely criticized. The perception that the judiciary is unwilling or unable to stand up to the executive has eroded public confidence in the institution. The independence of the judiciary is crucial for protecting fundamental rights and upholding the rule of law, and its erosion poses a grave threat to democracy. Such criticism is often dismissed as part of the “New India, New Normal” narrative.

Criminalization of Dissent

The mass arrest of political opponents marked the Emergency, but these were largely political detentions. In the Modi era, dissent is criminalized through the use of draconian laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and sedition laws. Activists, students, journalists, and ordinary citizens have been arrested for social media posts, peaceful protests, and criticism of the government. The use of these laws to silence dissent is particularly dangerous because it creates a climate of fear and self-censorship.

The right to dissent is a fundamental aspect of democracy, and its suppression undermines the very foundation of the republic. The targeting of dissenters as “anti-national” or “urban Naxals” has further polarized society and delegitimized opposition.

Use of Technology for Surveillance

Surveillance during the Emergency was largely physical and limited in scope. Today, the government has access to sophisticated digital surveillance tools. The Pegasus spyware scandal revealed that journalists, activists, and opposition leaders were being spied upon using military-grade software. This kind of mass surveillance threatens privacy, chills dissent, and undermines the very foundation of a free society.

The use of technology for surveillance is particularly insidious because it is often invisible. Citizens may not even be aware that they are being watched, leading to a chilling effect on free expression and association. The lack of effective legal safeguards and oversight makes it easy for the government to abuse its powers. The combination of surveillance, data collection, and control over digital infrastructure gives the government unprecedented power over its citizens.

Weakening of Parliamentary Democracy

During the Emergency, Parliament was suspended, but laws were still debated and discussed. In the Modi era, there has been a steady decline in the functioning of Parliament. Key bills, such as the farm laws and the abrogation of Article 370, were passed without adequate debate or consultation. The frequent use of ordinances, the suspension of opposition MPs, and the curtailment of parliamentary sessions have undermined the spirit of deliberative democracy.

The government’s reluctance to answer questions, the refusal to allow debates on key issues, and the use of brute majority to push through legislation have all contributed to the weakening of parliamentary democracy. The role of Parliament as a forum for debate, scrutiny, and accountability has been diminished. The result is a concentration of power in the executive, with little oversight or accountability.

Lack of Accountability: A Dangerous Precedent

Perhaps one of the most alarming features of the Modi era is the lack of accountability. In a healthy democracy, ministers and officials are expected to take responsibility for their actions. In the past, allegations of corruption or misconduct have led to the resignation of cabinet ministers and ministers of state. For example, Lal Bahadur Shastri resigned as Railway Minister after a train accident in 1956, accepting moral responsibility. In more recent times, ministers like A. Raja (2G scam), Ashok Chavan (Adarsh scam), and Suresh Kalmadi (CWG scam) resigned following allegations of corruption.

In the Modi era, however, there has been a marked reluctance to accept responsibility or resign in the face of controversy. As of a data in 2024, over the last five years, 351 persons died and 970 were injured in 200 consequential railway accidents. Anyhow, Nothing happened.

Ministers accused of misconduct or failure have been shielded by the government. The handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, the demonetization fiasco, and the farm laws protests are all other examples where the government has refused to accept responsibility or engage in meaningful dialogue with critics.

This lack of accountability is dangerous because it undermines the very foundation of democracy. If those in power are not held accountable for their actions, there is little incentive to act in the public interest. The absence of accountability also erodes public trust in institutions and the political process. Democracy is not just about elections; it is about the daily practice of accountability, transparency, and responsiveness to the needs of the people.

As the Basic Structure Continues to Be Compromised..

Most of the changes made during the Emergency were rolled back after 1977, and the democratic process was restored. In contrast, the Modi era has seen moves that may have long-term, irreversible impacts on the Constitution. The abrogation of Article 370, changes to citizenship laws, and attempts to alter the electoral process are seen as efforts to fundamentally reshape the Indian republic. These changes, critics argue, threaten the basic structure of the Constitution and could have lasting consequences.

The basic structure doctrine, established by the Supreme Court, holds that certain features of the Constitution—such as federalism, secularism, and the separation of powers—cannot be altered by Parliament. Legislative and executive overreach under the Modi government increasingly threatens these foundational features. The long-term impact of these changes may not be immediately apparent, but they have the potential to fundamentally alter the nature of the Indian state.

What makes the Modi era particularly dangerous, according to many analysts, is the slow and systematic nature of the changes. The Emergency was a declared, time-bound suspension of democracy. It was visible, and its excesses were widely documented. The Modi era, on the other hand, is marked by a gradual erosion of democratic norms, often under the guise of legality and national interest. This makes it harder to mobilize public opinion and resist the changes.

The use of technology, the co-option of institutions, and the targeting of dissenters have created an environment where fear and conformity are the norm. The government’s narrative of nationalism and development is used to justify actions that would have been unthinkable in earlier times. The result is a society where the space for dissent, debate, and diversity is shrinking.

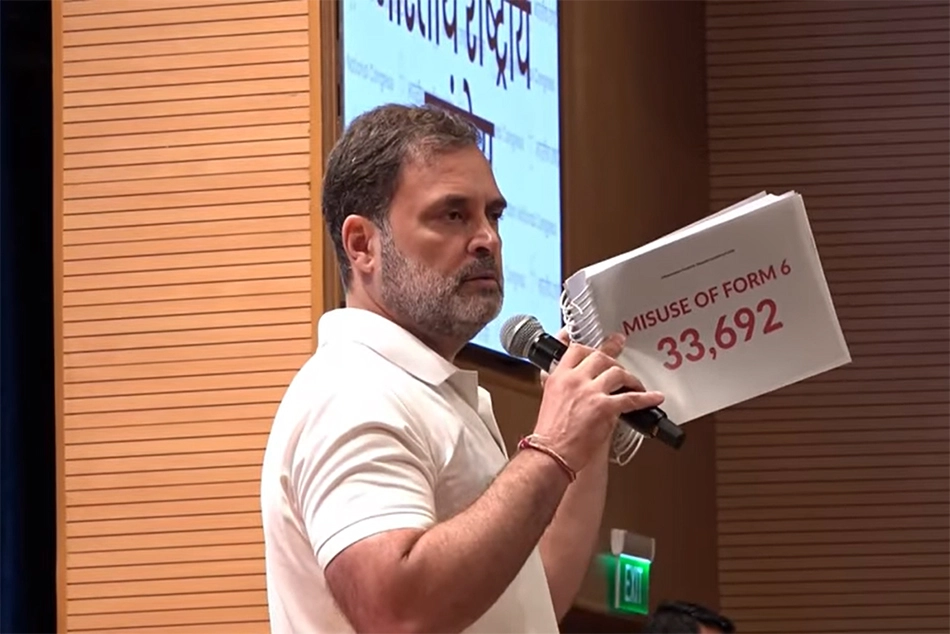

Now, with the Leader of Opposition openly accusing the BJP-led NDA government of election rigging, it’s clear that democracy’s health cannot be gauged by electoral victories alone. True democracy is defined by robust institutions, the safeguarding of minority rights, and the freedom for every citizen to speak without fear. When these pillars are weakened—when democratic norms erode, power is centralized, and accountability vanishes—it signals not just a crisis, but a fundamental threat to the very soul of the republic.

It’s true that the Emergency was a “mistake” and was a dark period in Indian history, but it was a declared and temporary suspension of democracy. But, the Modi era, is more dangerous because it represents a slow, systematic, and potentially permanent undermining of the Constitution and its basic structure. If the lessons of the Emergency are to be heeded, citizens, civil society, and the judiciary need to remain vigilant and defend the values enshrined in the Constitution. Indian democracy will endure not through the act of voting alone, but through our daily vigilance, our defense of dissent, and our collective will to uphold justice and liberty. It is we, the people, who must rise to protect the Constitution before silence becomes complicity.

[The writer, Adv Nabeel Kolothumthodi, is the Parliamentary Secretary to Praniti Sushilkumar Shinde MP, and an alumnus of the Faculty of Law, University of Delhi.]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic