Confusion Prevails in Bangladesh Over National Charter

The majority of people in Bangladesh are in the dark and groping in the wild to understand what the much-talked-about “July National Charter” is about, a political roadmap for democratic transition, at the behest of the Interim Government

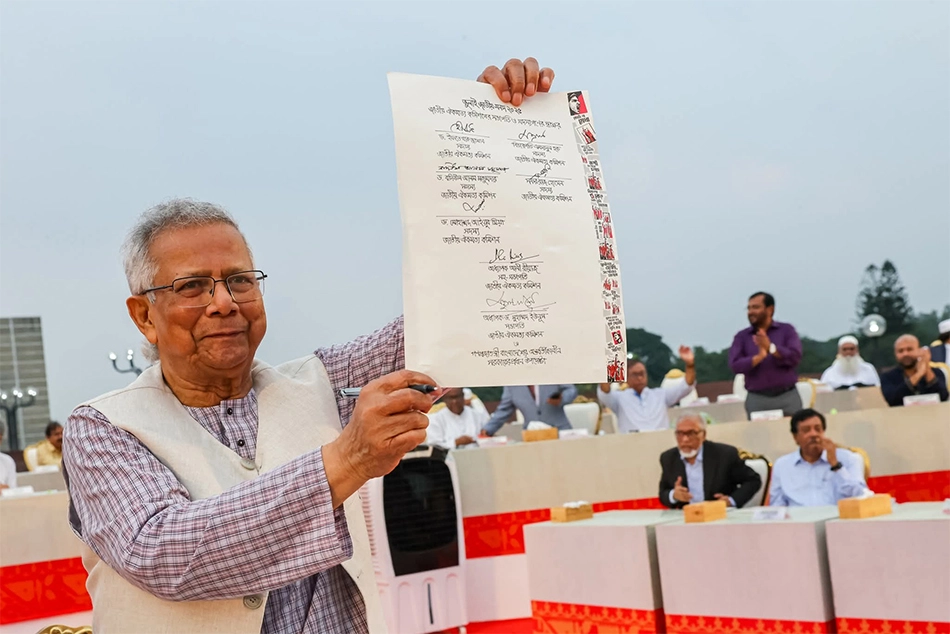

[Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser of the Interim Government and Head of the National Consensus Commission Bangladesh, signed the July National Charter on Oct 17, 2025 in Dhaka.]

The majority of people in Bangladesh are in the dark and groping in the wild to understand what the much-talked-about “July National Charter” is about, a political roadmap for democratic transition, at the behest of the Interim Government.

A genuine national consensus on the path to democratic renewal has fallen short of expectations. Uncertainty surrounding the Charter's implementation has left several political parties hesitant to sign, despite an eleventh-hour intervention by Chief Adviser Nobel laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus.

Many parties have shown themselves to be unable to bridge their differences over the nation’s future direction. Since the circulation of the final draft, some have questioned whether the exercise produced any meaningful consensus, wrote Kamal Ahmed, a columnist and former Chairperson of Media Reforms Commission of the Interim Government.

Last Friday, millions with access to national media, including television, newspapers, news portals, and social media, who are supposed to make informed decisions, plunged into a state of confusion over the new political roadmap.

Hasnat Quaiyum, president of the left-leaning Bangladesh Rastro Songskar Andolon, described the draft as “weaker” than the accord reached among the three alliances during the 1990s student uprising against former military ruler General HM Ershad.

However, the two major political parties - Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Awami League, in a see-saw to power several times, never bothered to bring about legislation in the parliament to implement the reforms agreed to in the joint declaration post-1990.

The Charter was named after the July-August Monsoon Revolution, which ousted autocratic Sheikh Hasina after 15 years of rule. A year ago, the street protests killed nearly 1400 young people in 36 days of Monsoon Revolution.

With the July Charter finally taking shape, Mohiuddin Alamgir of The Daily Star looks into the changes in the constitution, legislative structure, balance of power, and caretaker government system, as well as the new laws needed to reshape governance.

The Charter, born out of a compact among political parties, proposes a raft of constitutional reforms to reinvigorate Bangladesh’s parliament, which has remained weak and failed to function as an effective check on executive authority.

The proposals include the introduction of a bicameral legislature, a stronger opposition bench, institutional oversight, and checks and balances at the heart of parliamentary democracy.

Very few topics in Bangladesh’s political discourse have sparked as much debate or endured as long as the caretaker government system. To many, it represents not just a procedural framework but also a reliable means of conducting free and fair elections.

Introduced in 1991 through a rare political consensus, the caretaker system was widely accepted as a safeguard to ensure neutral elections, free from the influence of ruling parties. It was incorporated into the constitution in 1996.

Its unilateral abolition by the Awami League government in 2011 triggered a decade-long bitter dispute over an acceptable mechanism for holding credible elections.

The issue has emerged again with renewed urgency, as the July charter calls for the restoration of the system. Restoring the caretaker system with more safeguards in the charter has been stressed. Presently, the Supreme Court is hearing the abrogation of the caretaker government system.

Once the apex court renders a verdict on the cancellation of the system, Bangladesh will switch to the caretaker system mode. The Interim Government will cease to function 90 days before the election and hand over power to the Caretaker Government.

Reforms ahead of the national election have been the most consistent pledge of the interim government. One of the core reforms, apart from reviving the caretaker government system, is to bring about a balance of power between the prime minister and the president.

For years, critics have warned that the immense constitutional powers vested in the prime minister risk fostering authoritarianism, with the post of president remaining largely ceremonial, devoid of substantive authority.

The July Charter proposes curbing the PM’s overarching powers and strengthening the role of the president.

“To prevent the emergence of a fascist regime in the future, there must be a balance of power,” said Prof Ali Riaz, vice president of the National Consensus Commission.

Political parties have long stressed the need for a mechanism to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of the head of the government.

“Nearly all institutions are subject to the prime minister’s unilateral control. The president is constitutionally bound to act on the advice of the prime minister. In effect, the president holds no independent authority,” remarked Riaz.

Presently, the post of president is ceremonial. Real executive authority lies with the PM, who is the most powerful political actor with control over the executive, strong influence over the legislature, and indirect dominance over other state organs, wrote Alamgir.

Following its independence, Bangladesh adopted a parliamentary system of government. However, the country transitioned to a presidential form through the fourth amendment to the constitution in 1975.

The parliamentary system was reinstated in 1991, designating the prime minister as the executive head of the government and the president as the constitutional head of state. In reality, the president acts on the PM’s advice in almost all matters.

In an effort to curb the concentration of power in the Prime Minister’s Office, according to the charter, most political parties agreed that an individual may serve as PM for a maximum of 10 years. The PM will not be the leader of the ruling party in the parliament.

The charter proposes that a lawmaker would be barred from holding the office of PM and remaining party chief at the same time. However, BNP and several like-minded parties issued a note of dissent on the matter.

Not to the surprise of political analysts, the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islam always echoed the Interim Government’s election road map, without any question.

“The aim here is to create a degree of separation between the party and the government, thereby reducing the concentration of power in the hands of the prime minister,” Ali Riaz said.

“Plenty of theoretical ideas are there [in the charter], but what will happen in reality remains to be observed,” said Al Masud Hasanuzzaman, a former teacher of Jahangirnagar University.

Consensus Commission Vice President Ali Riaz said the overarching objective is to establish an accountable state and strengthen its institutions so that the country is not governed by the whims of any individual or group.

Kamal Ahmed, consultant editor of The Daily Star, concludes that the deeper divisions surfaced over contentious political questions. Disagreements persist over the powers of the proposed second chamber in parliament, eligibility criteria for its members, provisions for amending or suspending the constitution, appointments to key constitutional and regulatory bodies, the president’s impeachment process, nominating a deputy speaker from the opposition, and parliamentary ratification of international treaties.

[Saleem Samad is an independent journalist based in Bangladesh and a media rights defender with Reporters Without Borders. He is the recipient of the Ashoka Fellowship and the Hellman-Hammett Award. He could be reached at <saleem.samad.1971@gmail.com>; Twitter (X): @saleemsamad. The above article is dirst published in the Stratheia Policy Journal, Islamabad, Pakistan, 20 October 2025.]

Follow ummid.com WhatsApp Channel for all the latest updates.

Select Language to Translate in Urdu, Hindi, Marathi or Arabic